By Drew Roberts

Obsculta, o fili, praecepta magistri, et inclina aurem cordis tui

These are the words inscribed on the book held by the statue of St. Benedict in the church of St. Bernard’s Abbey. For those unacquainted with Latin, it means “Listen carefully, my son, to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.” For the monks residing at St. Bernard’s Abbey in Cullman, Alabama, it means everything.

The phrase comes from the prologue of “The Rule of Saint Benedict,” which guides Benedictine monks throughout the world in their day-to-day life. The rule has lasted for over 1500 years, ever since St. Benedict first established much of the monastic tradition we know today. St. Bernard’s Abbey is no exception, following this rule in everything they do and embodying the “ora et labora,” or “prayer and work,” so intrinsic to the Benedictine way of life.

St. Bernard’s Abbey, established by German monks traveling to Alabama, has been a mainstay of Southern monastic life for over 130 years. In tandem with the monastery, they run a school, St. Bernard’s Preparatory Academy, and lay claim to a pilgrimage site for many Catholics: the Ave Maria Grotto.

Abbot Marcus Voss and the Artistry of the Abbey

The man in charge of virtually everything at St. Bernard’s is Abbot Marcus Voss, the tenth abbot in the abbey’s history. A Cullman native, graduate of St. Bernards and the nephew of the Abbot Victor Clark, one could say he was born for this role. Voss first entered the monastery over 60 years ago and has remained there ever since.

That isn’t to say he was always sure of his vocation. In his early days, Voss faced challenges adjusting to the monastic life and presented his desire to leave to his uncle. Much to Voss’s surprise, his uncle agreed and encouraged him to leave. After further questioning, Voss discovered what his uncle meant: if he convinced him to stay, then something else would come up years down the road and make him want to leave. Voss needed to rediscover why he was at the monastery in the first place, something his uncle attributed to God’s grace in calling him there.

“[Abbot Victor Clark] said, ‘You’ve got to develop your own Jesus prayer: Jesus hear me, Jesus love me, Jesus forgive me, Jesus be with me,’ and I use it,” said Voss. “I use it. Whenever I have difficulties in my life I go back to that prayer.”

After this change in mindset, the Abbey became Voss’s home. He’s been able to witness it develop over the last six decades. His love for it can be seen most clearly in the attention he pays to it, specifically the church, which he witnessed the construction of so many years ago.

A tour through the church with Voss is like being guided through a carefully curated art museum. Every architectural decision was intentional. Golden light bathes the interior with a warm glow. Statues of saints, those from the New Testament in the seating area and those from the Old Testament behind the altar, line the walls. They are linked by a crucifix hanging above the altar, the image of Christ suffering facing the congregation during Mass and the image of Christ victorious facing the monks as they pray.

One of the more blink-and-you’ll-miss-it details of the church lies in the sandstone of the walls. For each block fastened into the wall, there exists a mirror image directly across from it. This was done to imitate the monk’s call-and-response style of prayer, seen when they face each other each time they gather.

“That’s how we function,” said Voss. “We echo back and forth constantly.”

Not all decisions were necessarily intentional, however. When a landscape architect arrived to install a handicap ramp for the church, he decided to walk inside. Out of curiosity, he measured the height of the altar to see what it lined up with. To his surprise and Voss’s, he found that the altar was the same height as the first floor of the school’s administration building.

Voss recalled the exchange, saying, “He said, ‘Your ora and labora are connected.’ He didn’t know it. I didn’t know it. It was really a revelation. I couldn’t believe it, and I don’t know if it was intentional or what, but as it turns out, these two are connected: our work and our prayer.”

Obedience: A Cardinal Virtue

Voss’s responsibilities as abbot require him to wear many hats. Whether it be attending to monks asking for vacation time or the day-to-day maintenance of the abbey, he has a hand in it. Just as he attends to the details of the church, he must attend to the monks obedient to him.

That vow of obedience is a central tenet of most Catholic religious communities, but in a Benedictine abbey, it carries even more weight.

Fr. Joel Martin, President of St. Bernard’s Preparatory Academy, finds a particular beauty in the practice of obedience, saying, “You may disagree with someone to whom you should be obedient, but as long as it’s not a sinful thing, you might think it’s a crazy idea, not sinful, but unwise perhaps. That obedience opens your life to something very wonderful, and that is surrendering your will for the good of the whole, for the good of the other.”

This idea of obedience is largely rooted in those original words from the prologue of the Rule of St. Benedict, the idea of “obsculta” or “to listen carefully.” The contemplative silence of the monks, the humble attitude towards work, and many other aspects of Benedictine life work to form a cohesive machine, inclining the ear of the heart to the divine.

“Obedience opens your life to something very wonderful, and that is surrendering your will for the good of the whole, for the good of the other.”

Fr. Joel Martin

“Benedictine life, obedience, listening by humility, really does make us open and available to do the work of God and [see] how He works through human beings,” said Martin. “That way has in essence, changed the world, like Benedict did. All he wanted to do is found this school for the Lord’s service within a monastery without outside interaction, but it ended up truly changing the world, preserving life as it was passed down to us, culture and so forth, and all that happened from someone who just wanted to serve God in a life of prayer and work.”

From its long history of copying manuscripts, monasticism, particularly the Benedictine flavor has placed a strong emphasis on the preservation of Western culture. A scientist from NASA even made the argument to Martin that the Benedictine rule and its cultivation of Western science got America to the moon. This focus on cultivating and preserving Western history and values can be seen through the educational ministry at St. Bernard’s, but also in something more tangible: the Ave Maria Grotto.

Br. Joseph Zoettl and the Ave Maria Grotto

Standing less than five feet tall, Br. Joseph Zoettl was relatively unassuming. He had immigrated to Cullman from Bavaria and had dreams of the priesthood. This dream, however, was never realized. While performing construction, a bell fell on his back and left him with a hunchback for the rest of his life. This hunchback gave the already distinctive monk a definable characteristic, one that the abbot feared would bring undue attention to him. The black robes of the Benedictines emphasize uniformity, each monk submitting to the work of the order.

When the abbot forbade him from become a priest, Zoettl submitted. It was a new cross, one that Zoettl excepted with humility. Nonetheless, a silver lining presented itself. Without priestly duties, Zoetl had much more time on his hands. He began to pick up discarded items and bring them back to his workshop. He tinkered away for hours, crafting the original structures that would come to make up the Ave Maria Grotto.

Originally dubbed “Little Jerusalem,” the grotto features scenes from the Bible, churches throughout the world and so much more. The details in each structure, gently placed by the hands of Zoettl, are all part of an artistic ecosystem that has drawn Catholics worldwide to Cullman.

Zoettl is buried in the abbey cemetery alongside who Voss affectionately referred to as “the happy monks.” Unlike the other monks, the cross that serves as his headstone is adorned with a small array of rocks and coins presumably placed by visitors.

Though his dreams of being a priest never came to fruition, the indelible mark Zoettl created through the grotto has made St. Bernard’s a place of pilgrimage for decades.

Unintentional Educators

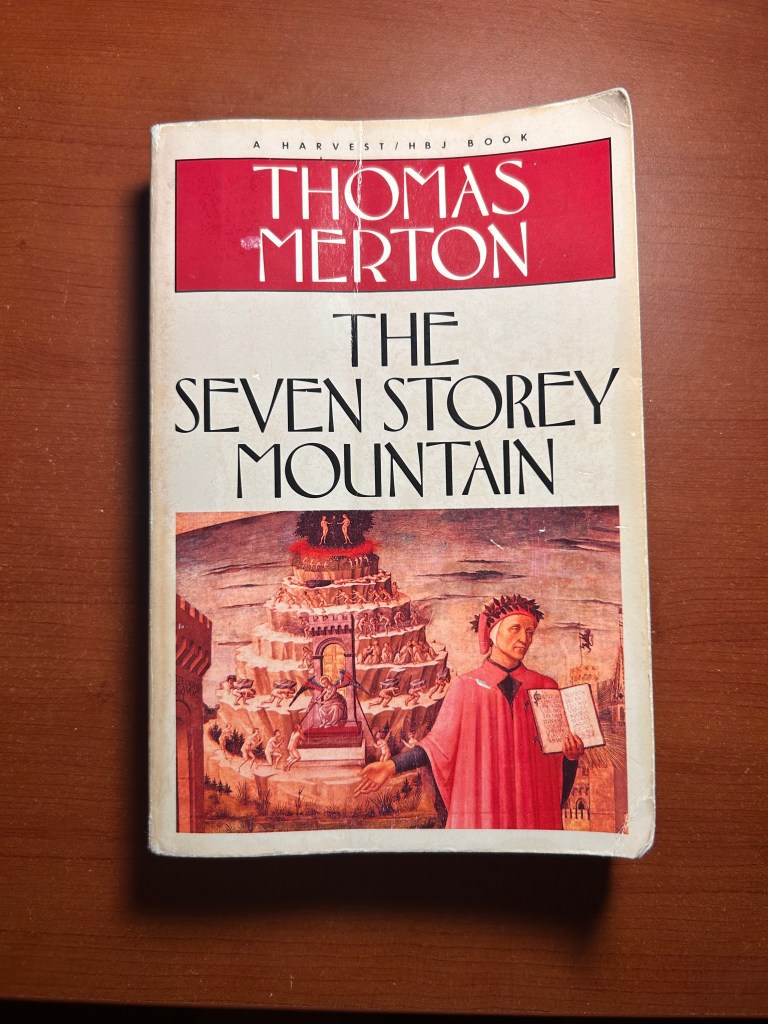

Fr. Joel Martin did not want to work in a school. In fact, he deliberately sought out abbeys that didn’t have one. Thomas Merton, Trappist monk and famed author of “The Seven Storey Mountain,” declared that the reason he didn’t become a “black Benedictine,” but instead joined the stricter order of the Trappists was because he didn’t want to work in a school. Though not desiring to join the Trappists, Martin shared Merton’s opinion.

“Thomas Merton became sort of the expert in monasticism for a lot of people,” said Martin. “That’s what he was for me.”

The Trappist order that Merton belonged to is also known by another name: The Cistercians of the Strict Observance. They felt that many Benedictine circles had grown too lax in following the Rule of St. Benedict, even going so far as to wear white robes after judging that the black dye of the typical Benedictine robes was wasteful. Thus, the terms “black Benedictine” and “white Benedictine” were born.

The secular governments of many countries forced their monasteries to add something productive to society. Martin noted that prayer was not one of those things. In order to survive, the “black Benedictines” started to run schools and promote education. Cistercians, on the other hand, followed more closely to the simple life of prayer and work.

St. Bernard’s had a school during Martin’s process of discernment, but ultimately decided to close it. Relieved by this news, Martin decided he’d join. In an act of divine irony, however, the school reopened the year Martin entered the novitiate. It was “a joke of some sorts” according to Martin, and he contemplated leaving. Yet just like Voss in his early monastic years, Martin elected to stay.

Martin has now been serving St. Bernard’s Preparatory School for over 40 years. He currently serves as president and strives to cultivate Benedictine principles in the classroom.

“A big part of what we like to teach in a Benedictine school is that is to listen, to be open, to be aware of and to inculcate in our lives by listening, the wisdom, the precepts, the teachings of the master,” said Martin. “That humility is a very powerful thing. Of course it’s necessary for learning. It’s necessary for being open to God, and to be receptive just to ideas and to the thoughts of those who have something to pass onto us. Benedictine life is very much about receiving what has been handed on to you and being humble enough to receive that. In that humility and being able to receive, being able then to have the courage to do something with your life and make your life count.”

It’s Martin’s goal to provide a quality, faith-centered education to “those who can afford it and those who cannot.” He feels that as society has grown more pluralistic, there is less room for God in public education.

“I would say public schools teach more about what they don’t teach than about what they do,” said Martin. “And that absence is very loud in how it teaches people in the culture that what’s really important is what you learn in school, and that has nothing to do with God or the faith.”

In his tenure at St. Bernard’s, Martin has witnessed faith in action and grace come to the most unlikely of students. He thinks of one such student quite a bit. While at St. Bernard’s, this student rebelled against and questioned much of what he was taught in class. Yet, he had a particular fascination with the Russian language and culture and eventually moved there to teach.

This surprised Martin, who assumed the entire Russian endeavor was just the dream of a teenager. What surprised him even more though, was seeing a photograph of the now young man in Russia. An “explosion” of hair sprouted from his head and the camera captured his shirtless back as he stared into the distance. Tattooed on his back was the symbol of the ouroboros, depicting a snake eating its tail, that has significance in many Eastern religions. Inside the snake was writing in Russian that Martin couldn’t decipher.

“I looked at that sight: the hair, the snake and I couldn’t imagine what he had written on his back inside that snake!” said Martin.

Martin then took the photo for a Russian woman in town to decipher. What she told him may have been the last thing he expected. Inside that snake were the words of the 24th verse of the 12th chapter of the Gospel of John: “Amen, Amen, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat; but if it dies, it produces much fruit.”

Martin was shocked, saying, “Here is that boy that I was expecting the worst from and he had imprinted on his body for the rest of his life really the heart of the Gospel and what Christians believe, the hard stuff too.”

The Benedictine life, despite all of its routines and procedures, is still one of adventure, unexpected turns and new challenges. When Marcus Voss wanted to leave the monastery, Joseph Zoettl lost his dream of becoming a priest and Joel Martin found himself in an originally undesired vocation, they all appealed to the simple of words of St. Benedict, inclining the ears of their heart and listening carefully.